How can designers get better at learning from their mistakes

Our ability to learn when things go wrong is what helps us grow. Not just as individuals but as an industry. By better understanding when our ego clouds our better judgement, when we’re pointing fingers, or when we have to kill our darlings, we can always improve.

This is the second in a two-part series on learning from failure in design, and a summary of my talk given at WAQ18 in Quebec City, Canada.

Here are 7 things designers can take into their workplace to improve the way they and their design teams learn from failure.

Build a culture to learn from mistakes

Arguably the biggest challenge first, a healthy failure-accepting culture creates the best bedrock for growth.

Looking at the likes of Toyota and the British Cycling Team, neither of these organisations could become successes if their cultures had fear, loss aversion and ego as the main drivers for growth.

As the famous Peter Drucker once said:

Culture eats strategy for breakfast

An organisation’s culture beats any business plan, and becomes the fabric by which the company operates. By creating a culture of positivity and failure acceptance, you’ll be rewarded for years to come.

Embrace healthy critique

A surefire way of kickstarting a culture of accepting failure is through regular design reviews or critiques.

Design reviews can be daunting, humbling and a bit painful. But some of the biggest strides I’ve made as a designer were through regular design reviews at Clearleft.

Every designer makes mistakes. It’s normal. /Genius design doesn’t exist/, and design by definition is iterative. Holding regular design critique sessions democratises the design process, crowdsources the right solution and identifies areas for improving.

Fail little and often

Our ability to create low-cost prototypes and test with users is part of what makes the digital design industry so cutting edge. The very concept of a prototype is to see where things have gone wrong.

The Design sprint, made wildly popular by Jake Knapp and the Google Ventures team, espouses the virtues of how valuable being wrong can be.

Some of the most successful design sprints I’ve been a part of are ones where an idea is proven wrong, not right.

By highlighting an idea’s insufficiencies, shortcomings or non-viability, the organisation might have saved thousands in lost capital. Alternatively, the learnings from the failed idea might spark new, better ideas that have now been validated.

Listen to users

User testing is perhaps the best embodiment of McGrath’s /‘intelligent failure/’ concept that we as designers have at our disposal.

Consider user testing versus McGrath’s four pillars of intelligent failure. User testing is:

- Carefully planned

- The risks aren’t too great

- The downsides are controlled

- There’s a mechanism for sharing the learnings

By knowing where — and more importantly, why — a feature, flow or similar has failed with users, designers can learn, adapt and iterate on their original solution.

Routine, regular user testing sessions allows everyone across an organisation to learn what works and what doesn’t. It instills a culture of accepting failure as part of the design process. Many tech firms have adopted specific, weekly sessions (’Testing Tuesdays’) to help foster a culture of learning from failure.

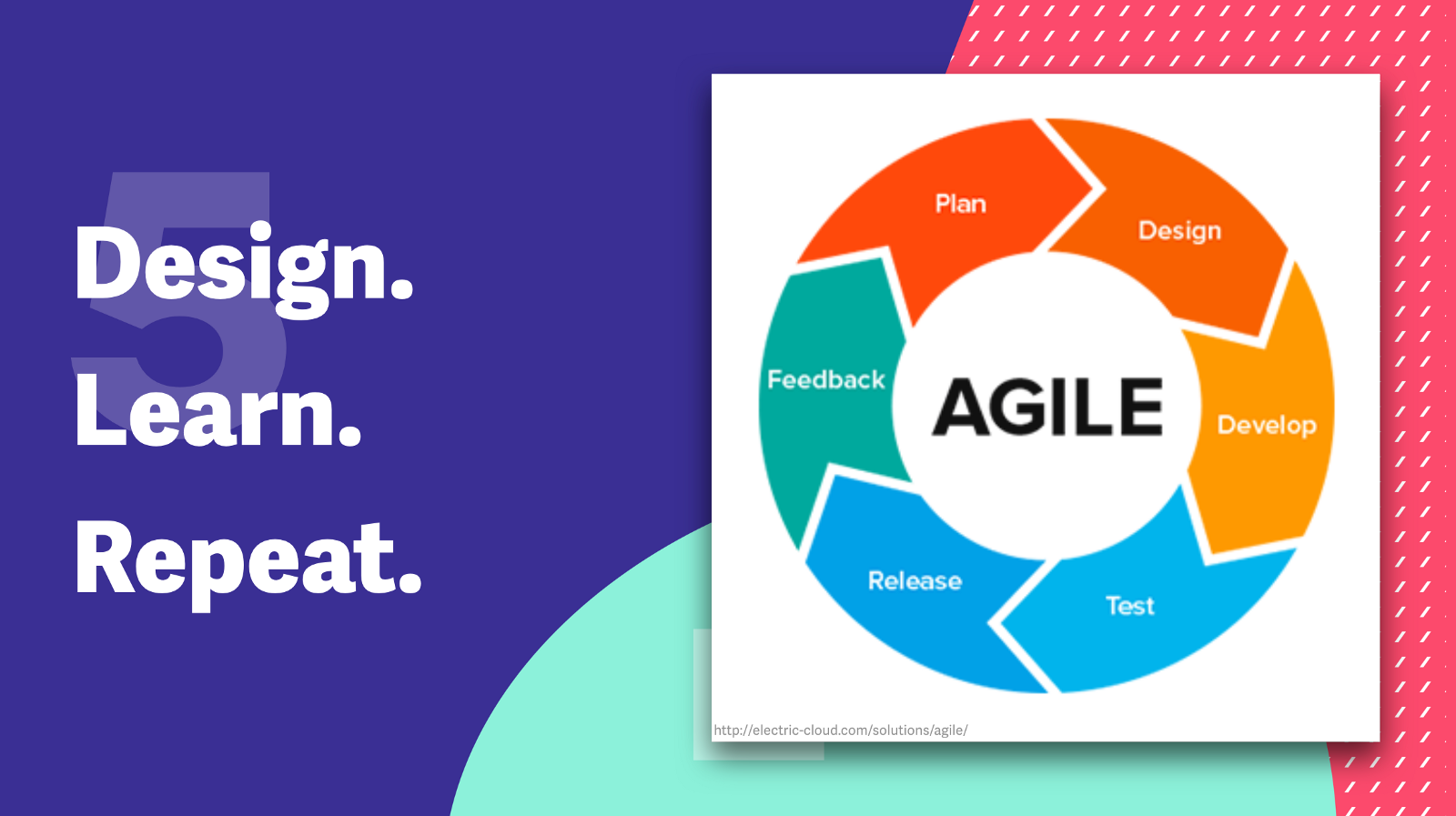

Design. Learn. Repeat

Many design teams are running in agile — or some blend of it — to release new features to their digital products.

Whilst many aspects of agile are already well-equipped to help us rapidly iterate and innovate, the agile methodology comes pre-packaged with one of the best tools for learning from failure we have: the retrospective.

Retrospectives occur after each agile sprint, and ideally once after the project finishes or the product is released (a project wash up). They consist of three core questions, answered by the entire team:

- What went well

- What needs improvement

- What are the next steps

In Syed’s book Black box thinking, the concept of a black box was used as a metaphor for intelligent failure. Aviation experts who sought answers in the face of failure helped avoid making the same mistakes again.

Retrospectives are a design team’s collective opportunity to understand what went wrong and how to avoid past mistakes. Holding regular retrospectives during a project can help to build a positive, failure-tolerant culture. Regular retros also become the design team’s black box. By uncovering truths about the project and shedding light on the aspects that can be improved, the capacity for learning is extensive.

Create a shared understanding

The concept of a ‘shared understanding’ was coined by Jeff Patton, the author of agile’s often used user story mapping method.

Patton’s idea shifted the focus away from requirements living in a document to story-based user narratives. These stories reflected a user’s needs from a product. The story telling component helped product teams create a shared understanding of what they were creating, and how it benefitted the end user. The use of storytelling in this context made it easier to communicate across teams without the loss of information fidelity.

It’s this shared understanding that helps safeguard organisations from repeating past mistakes. From near-misses to newsworthy tragedies, the aviation industry shares the outcomes of any investigation across all airlines. It’s this shared understanding (and collective learning) that resulted in 2017 being the safest year on record for commercial air travel, with zero accident deaths recorded.

If the findings of regular retrospectives aren’t shared across the wider organisation, the mistakes made are likely to be repeated.

A great way of sharing learnings is by holding regular information sharing sessions. At Clearleft we held brown bag lunches, an informal and weekly session where the learnings from newly-finished projects could be shared with the wider team.

This knowledge transfer is invaluable. By sharing the pains (and the wins) of a project, colleagues, bosses, product owners and peers can avoid repeating the same mistakes.

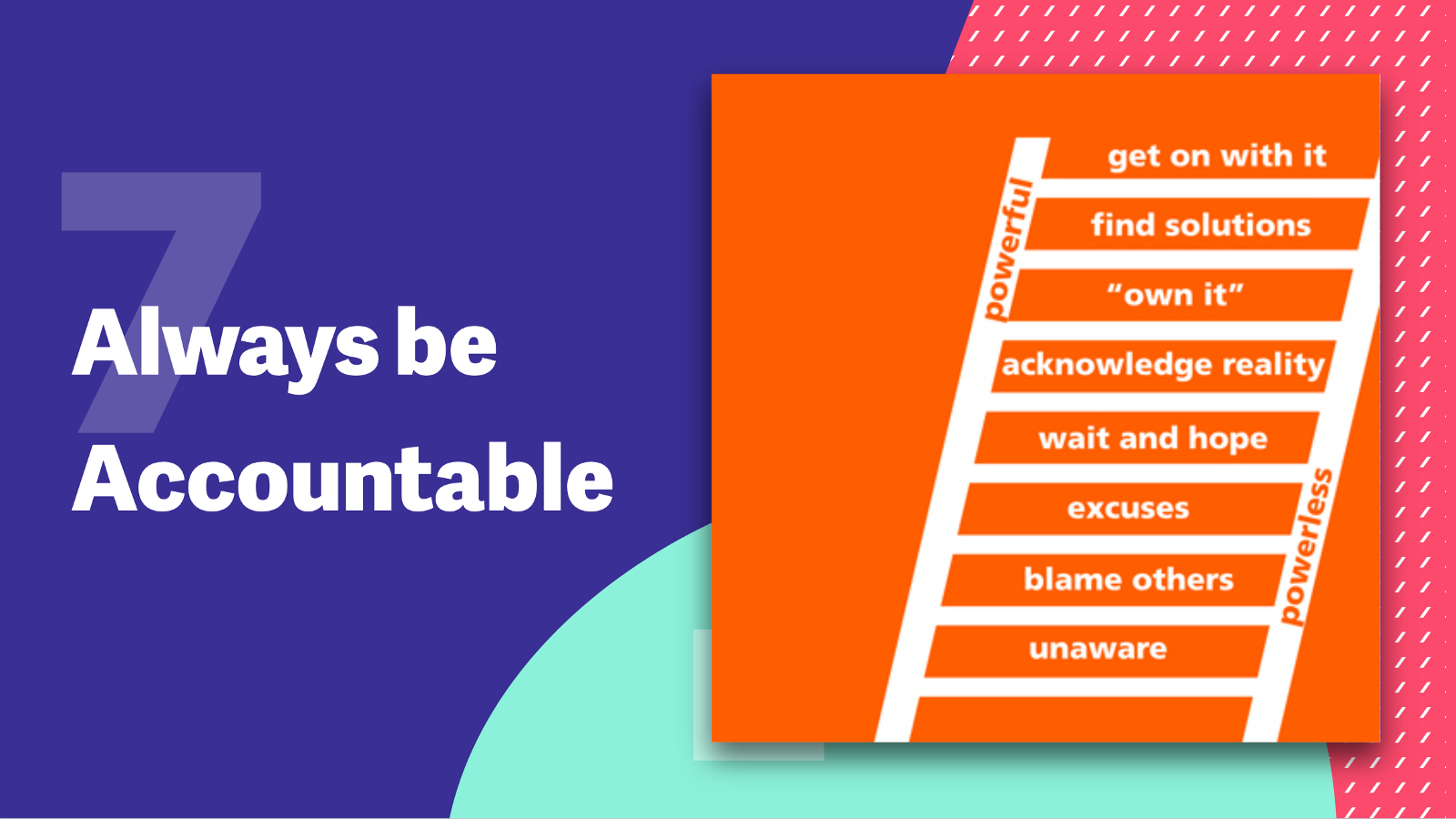

Always be accountable

Being accountable means accepting when things go wrong and striving to prevent them from happening again.

If ego, cognitive dissonance and the fundamental attribution error all erode a designer’s ability to learn from mistakes, then taking accountability helps build it back.

Embracing critical feedback. Preventing ego from clouding better judgement. Avoiding the propensity to blame others when things go wrong. These are all examples of designers taking accountability for when things go wrong.

The accountability ladder (above) sees designers who tend to lay blame positioned on the lower rungs. As they become more accountable they move from a powerless position to one of power and autonomy. As we collectively find solutions to our past mistakes, we level up — both as individuals and as an industry.

You’re going to fail, so do it smartly

Failure should be accepted and respected. We’re all likely to fail at something in our careers. Some of those mistakes will be small and trivial while others can have far-reaching consequences.

How we deal with either is integral to our growth. Failure need not be stigmatised or avoided. The best ways to learn from our mistakes is to create a strong culture where failure is seen as part of the natural order to good design.

As designers we have several methods and processes available to us to better learn from our mistakes, but often we let ego, pride and subjectivity cloud our judgement. We need to make better use of our incredibly open and unique industry to share our war stories. It’s these moments of learning that can benefit our colleagues, peers and clients alike.

We need to collectively move away from being gut-reacting, ego-driven designers to objective, intelligently-failing professionals who want to create the best possible experiences for our end users. Retrospectives are one of the strongest tools we have at our disposal to begin acting more like aviation experts and their black boxes, rather than doctors protecting their egos and pride.

This article was originally published on Medium and Prototype.io

July 30th, 2018